The anglerfish is truly an odd creature. It lives at extreme depths, where over 2,000 PSI of pressure would prevent most aquatic creatures from surviving. There is hardly any light at these depths, so there is no photosynthesis, and scarcely any large autotrophs to provide nutrition for large animals, so animals are almost always carnivores at these depths. An exception to this rule would be the deep-sea tubeworms covered in one of my earlier posts.

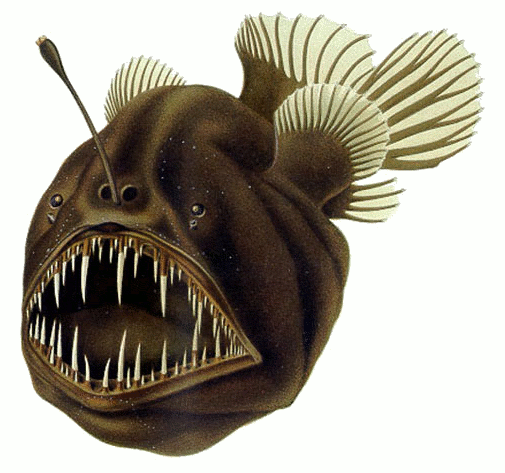

The carnivores that live at these depths compete fiercely for the available food because it is so scarce, and they demonstrate some of the most extreme adaptations towards a carnivorous lifestyle. Those fearsome teeth are not for decoration. They are very special pointed teeth that are inclined inwards—to prevent whatever enters from leaving. The enormous jaws of the anglerfish extend around the anterior circumference of its head, and its thin and flexible bones allow it to swallow very large prey. In fact, the Monkfish, another lophiiforme and close relative of the Anglerfish can swallow prey larger than itself, obviously not demonstrating monk-like temperance towards food.

A truly outstanding predatory feature of the anglerfish is its bioluminescent “lure” that it dangles in front of its mouth to attract prey. There is virtually no light at the depths anglerfish live, so their bodies are almost invisible to other fish. The lure, like the tubeworm, uses symbiotic bacteria to function. The chemical reaction involved is quite unique in nature, relying upon an enzyme called luciferase and a photoprotein. The luciferase catalyzes a reaction between the photoprotein and calcium ions. It is unclear how the actual mechanism works, but photons are emitted. This is completely unlike florescence or phosphorescence, where certain materials absorb photons and undergo energetic transitions and occasionally release photons. Bioluminesance requires no incident light.

The most interesting feature of the Anglerfish is the extreme sexual dimorphism demonstrated by the species. When scientists first started catching Anglerfish, they noticed every specimen was female. They wondered, “Where are the males?” It took them a while before they discovered small parasitic organisms living on the female’s body. It turns out these are the boys.

Male anglerfish hatchlings (called fry) have no digestive system, and are unable to feed. Fortunately they are equipped with extraordinarily sensitive olfactory organs (like the male lamprey) that detect female anglerfish pheromones (also like the lamprey). When a male locates a female, he bites into her side and fuses with one of her blood vessels to receive nourishment. This merging of two different adult organisms' body tissues is extremely unusual and largely unexplained.

The male then undergoes gradual atrophy until his body is noting more than a pair of gonads that release sperm in response to hormones in the female’s body indicating egg release. I would like to send a pet Anglerfish (complete with high-pressure aquarium) to every radical feminist in the world. Perhaps reflection upon the plight of the male anglerfish would provide them with enough satisfaction that they would be able to cease their antagonization of men. Also, the not-very-ladylike behavior and appearance of the Anglerfish female will surely provide them a model to strive for.

Jest aside; this is truly remarkable sexual dimorphism. Surely everybody has noticed that roosters look and act a bit differently than chickens, that bulls are different than cows. The Anglerfish takes this to an extreme. Various explanations have been lodged to explain this. One is that Anglerfish, living lonely lives in the depths of the ocean, rarely encounter each other. The infrequency of their encounters makes sexual reproduction costly. Atrophied parasitic males attached to the females solve this “meeting” problem handily. Also, females are not always fertile, making timing the encounter important. Most animals solve this with a breeding season, but there are no seasons in the depths—it’s cold and dark all year. The Anglerfish solves this problem because the male is always available for sex. Actually, he basically is a sex organ. This dimorphism also greatly conserves food. Since food is so scarce down there, why waste much of it on males that cannot generate offspring? It makes a lot more sense to have the female consume almost all the food.

Upon reflecting on the creatures I have described in my canon of oddities, I think I should have titled the series Nature’s Eccentricities. Odd carries a bad connotation, and every creature I have listed is certainly highly successful in its little niche.

>

>